“It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos.”

Meet General George Catlett Marshall

General George Catlett Marshall is considered by many to be one of the greatest modern-day Americans. He is recognized as the organizer of the Allied victory in World War II and the architect of the European Recovery Program (the Marshall Plan) that changed the face of the world and earned Marshall the Nobel Peace Prize. From the beginning of his 45-year public career as a graduate of Virginia Military Institute in 1901 to recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953, Marshall received more than 60 decorations, awards, and honorary degrees, including military, civilian, and substantial foreign recognition.

Amid his extraordinary accomplishments, Marshall was most appreciated and beloved for who he was. He earned an uncontested reputation for being an honest, humble, and resolute leader and did not seek fame. His personal contributions to the efforts and development of the United States and other countries during some of the most significant events in modern history are remarkable, not just for the magnitude of what he accomplished, but because of the incorruptible, selfless integrity with which he served.

The Life of A Great American

1880. George C. Marshall is born in Uniontown, PA.

1901. Graduates from the Virginia Military Institute as Cadet First Captain and Regimental Commander. Begins a 45-year Army career.

1917-1919. Second American to step ashore in France during World War I. Serves as Operations Officer and Aide to General John J. Pershing.

1939. Promoted to four-star general; sworn in as U.S. Army Chief of Staff on the same day Hitler invades Poland, launching World War II.

1940-1941. Katherine Marshall visits Leesburg, VA and pays $10 earnest money to purchase Dodona Manor. Attack on Pearl Harbor forces the U.S. into World War II, postponing Marshall’s retirement plans.

1944. Promoted to five-star general, as the tide turns in Europe following D-Day.

1945. Winston Churchill calls Marshall the “organizer of victory” after the war ends in Europe. Marshall hopes to retire from the Army to Dodona Manor. Within weeks, he goes to China as President Truman’s Special Envoy to mediate the civil war.

1947. Unanimously confirmed as Secretary of State. Delivers speech at Harvard outlining idea of a monumental economic aid package for Europe.

1948. The European Recovery Program (Marshall Plan) becomes law, beginning historic economic aid and cooperation with 17 war-ravaged nations.

1949. Serves as President of the American Red Cross; travels extensively to restore morale and strengthen the world’s most essential humanitarian organization.

1950. President Truman visits Dodona Manor, requesting Marshall to return to the national service; appointed Secretary of Defense during the Korean War

1953. Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for the Marshall Plan, the first career soldier to receive the award.

1959. George C. Marshall dies at age 78 and is mourned worldwide before being buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

1989. The George C. Marshall Home Preservation Fund, established by local citizens, preserves General and Mrs. Marshall’s home from destruction. This paves the way for the creation of the George C. Marshall International Center to support educational programming based on General Marshall’s legacy.

2005. Dodona Manor opens as a historic house museum of the 1950s.

Marshall’s Youth

In the first installment of Marshall’s Youth, historian Rachel Yarnell Thompson shares some insightful stories from George C. Marshall’s boyhood. In this chapter, we learn about George’s parents and his immediate family in Uniontown, Pennsylvania. Learn about some of the humorous boyhood mischief that George got himself into -- and the roots of some of his defining characteristics.

From a gardening contest to their family’s reversal of fortune, Marshall’s childhood in Uniontown is full of surprises and lessons. This episode shines a spotlight on Marshall’s mischievous, yet promising beginnings.

The second episode of Marshall’s Youth paints George C. Marshall’s teenage years, quirks, and influences. Thompson recounts the interactions that would shape Marshall’s personality and thirst for learning, from an Episcopal reverend to a church organist to even Blackbeard the Pirate.

Thompson’s description of Marshall’s youth is not complete without discussing his boyhood mannerisms and blunders. The second episode also talks about Marshall’s time in public school. Although not known as the most achieving student in his local school, Marshall’s attempts at meeting his father’s academic and social standards are on display.

Upon entering the Virginia Military Institute, George Marshall began growing into the composed leader history would remember him. During his time at VMI, he quickly rose from a freshman “rat” to the prestigious position of First Captain. He also found time to fall in love with a local girl.

There was a deep motivator behind his many successes at VMI and beyond. Marshall was focused on overcoming discouragement from his own family. His older brother, Stuart, confided in his mother that if Marshall were to enlist at VMI, this would “ruin the family’s reputation.” Undeterred, Marshall entered VMI with something to prove. As history shows, he proved them wrong and more.

Early Career

George C. Marshall was born December 31, 1880, in Uniontown, PA, into the family of a prominent local businessman whose company manufactured coke ovens and who participated in real estate ventures. His comfortable childhood was filled with episodes of fun and mischief, shaped by the love and discipline of his parents.

In his early education he was a lackluster student, but later when he overheard his older brother Stuart beg his mother not to let George go to the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) because he thought it would disgrace the family name, George was inspired to outshine his brother.

His career at VMI was marked by an uncommon determination to excel, and in his senior year he was selected as First Captain of the Cadet Corps, the most honored position in that institution.

1902 – 1929, The Beginning of a Military Career

George C. Marshall obtained his commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army in 1902. Immediately after receiving his commission he married Elizabeth “Lily” Carter Coles, his college sweetheart from Lexington, VA.

His first assignment was with the 30th Infantry in the Philippines, part of the U.S. occupation to quell an insurrection by natives. This assignment in leading troops in combat was the beginning of a long career of learning the many duties and functions of an Army officer, vital to an officer destined to achieve the highest rank in the service. His duties prior to World War I included service in mapping remote parts of Texas, a stint as student, and later as instructor at Fort Leavenworth’s officer Staff School. As the top student in his class, his subsequent assignment as a Leavenworth instructor was a distinct honor indicative of his evident potential. This was the first of many key teaching assignments that marked his military career.

His assignment with the Massachusetts National Guard, and duty with the 4th Infantry at three different military bases gave him insight into the range and structure of the U.S. Army in peacetime. His duty as aide-de-camp to Gen. Hunter Liggett in the Philippines and later to Gen. James Bell in the U.S. afforded him invaluable experience in effective staff work that would eventually propel him to a position that proved to be his forte in World War I and later years.

His assignment as Assistant Chief of Operations for the 1st Division in France in 1917 gave him the opportunity to distinguish himself amongst the senior Army leadership as one of the most promising staff officers in the command. Ironically this opportunity arose as the result of a characteristically Marshall reaction to what he perceived as an injustice. His challenge of the formidable Gen. John J. Pershing in front of the 1st Division staff for his unfair criticism of the division and its commander (Maj. Gen. William Sibert) was unprecedented conduct for a middle-grade officer. His crisp and meticulous critique of the failings of Pershing’s General Staff that had undermined the division’s performance stunned General Pershing and the assembled staff.

Pershing said nothing. He departed abruptly, and Marshall’s peers thought that his career was over. But Marshall’s determination to speak “truth to power” proved an incalculable asset to his superiors and belied the pervasive belief that unvarnished candor to superiors was career suicide. Marshall’s honesty and intellectual rigor soon earned him appointment to the Operations Staff of the General Headquarters. He drafted the operations order moving 400,000 American troops from the St. Mihiel salient to the Meuse-Argonne offensive to join some 200,000 Americans already engaged in a complex 72-hour movement. Marshall’s order was viewed as a masterstroke of brilliant staff work and marked him as a likely future Chief of Staff of the Army though he was then only a lieutenant colonel.

After the Armistice, Marshall remained in France as Chief of Staff of the 8th Army until he was selected to be General Pershing’s Aide-de-Camp. As such, he accompanied Pershing on a victory tour of the Allies’ capitals that which gave him the opportunity to meet several of the individuals who became prominent leaders in World War II. His service as Pershing’s ADC while the latter served as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army provided Marshall insight into the Army’s dealing with a presidential administration, the federal bureaucracy and, most importantly, with the Congress. In 1924 when General Pershing stepped down as Chief of Staff, Marshall was named Deputy Commander of the elite 15th Infantry in Tientsin, China.This was one more assignment during which he could expand the scope of his acquaintance with promising officers and evaluate those who did measure up, a sort of virtual “black book.”

This methodical process of observation became a part of the critical personnel decisions that Marshall would have to make when he rose to command the U.S. Army as it mobilized for World War II. It was at the end of this tour in 1927 that Lily Coles, his beloved but frail first wife, died. After her death, he was given the choice of three posts, and he opted to be Assistant Commandant at the Fort Benning Infantry School, another excellent vantage point to expand and refine his “black book.”

It was in that assignment that George Marshall made one of his most enduring contributions to the Army by promoting the reformed infantry doctrine and training to replace infantry attacks in mass formations with assault by small units by fire and maneuver. He revamped training methods to keep operations and orders simple, to provide officers flexibility in responding to changing situations, and to concentrate on field exercises in lieu of lectures. This change in tactics and training saved thousands of American infantrymen’s lives in World War II, which was a war of movement, as opposed to one of static defense that he had observed from the front in World War I. During Marshall’s five years at Fort Benning, 150 future World War II generals passed through in training, and some 50 more future generals served on the Infantry School’s staff.

1930 – 1939 From Fort Benning to Chief of Staff of the Army

While at Fort Benning, in October 1930, Marshall courted and married Katherine Boyce Tupper Brown, a Baltimore widow with three young children. His subsequent assignments with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in Georgia and South Carolina in 1932 and 1933 gave Marshall a window into the character and ability of young American men who would serve in his citizen army in the coming war.

Following his service with the CCC, he returned to a recurring role in his life, that of teacher serving as the senior instructor with the Illinois National Guard. His focus in his tour from 1933 to 1936 was to apply his infantry training concepts to the poorly motivated and inadequately trained National Guard units in recognition that the citizen-soldier would carry the burden in any future war. He concentrated his efforts on enhancing the professionalism of the Guard soldiers, and especially of the officers. He also developed staff structures for the Guard while making unit training more realistic and more efficient. He also pressed the Army to assign higher caliber officers to all the state National Guard commands. Marshall’s promotion to brigadier general in October 1936 was, as he recognized, and for which he had gently campaigned, an essential step toward realizing his interest in becoming Chief of Staff of the Army.

His promotion earned him command of the 5th Brigade of the 3rd Infantry Division and the position of post commander of Vancouver Barracks, just north of Portland, Oregon. This proved to be a satisfying assignment for him both professionally and personally. In addition to obtaining a long-sought and significant troop command, traditionally viewed as an indispensable step to the pinnacle of the U.S. Army, Marshall was also responsible for 35 CCC camps in Oregon and southern Washington.

As post commander, Marshall made a concerted effort to cultivate relations with the city of Portland and to enhance the image of the U.S. Army in the region. He initiated a series of measures in the CCC to improve the morale of the participants and to make the experience beneficial in their later life. He started a newspaper for the CCC region that provided a vehicle to promote CCC successes, and he initiated a variety of programs that developed their skills and improved their health. Marshall’s inspections of the CCC camps gave him and his wife Katherine the chance to enjoy the beauty of the American Northwest and made the assignment what he called “the most instructive service I ever had, and the most interesting.”

George Marshall arrived in July 1938 at his new assignment as Head of the War Plans Division at Army Headquarters in Washington, D.C. While Marshall was widely regarded as a brilliant staff officer, he regretted giving up his troop command and the satisfaction of working with the CCC in the magnificent setting of the Northwest. War clouds were gathering in Europe as Hitler’s aggressive actions slowly began to persuade European democracies that they could be constrained only by the use of force. Concurrently, Japan pursued its conquests in China and threatened other Western interests in the Pacific. Distasteful as it was for Americans, war planning became essential, and Marshall was clearly the officer to lead these efforts. Within three months, he was elevated to the Deputy Chief of Staff position. In this capacity he attended a White House conference in November 1938 that proved a fateful encounter that shaped not only his career, but also the course of American history in the 20th Century.

At that council of his senior advisers, President Franklin Roosevelt proposed to build 10,000 aircraft for European democracies to forestall U.S. involvement in the impending war. Marshall was stunned by the proposal which made no provision for training of flight crews and other logistical challenges. More importantly, that initiative would be at the expense of America’s need for more troops, tanks and all the other material required to prepare for war. When Roosevelt asked the attendees for their reaction, Marshall was astounded that all of his military colleagues assented to a proposal that they did not agree with.

When the President came to Marshall, he asked, “Don’t you think so, George?” Marshall, who was attending his first conference with Roosevelt, was vexed at the President’s “misrepresentation of our intimacy” by the use of his first name. Nonetheless, he firmly replied, “I’m sorry Mr. President, I don’t agree with you at all.” This apparently startled the President and the meeting adjourned abruptly. As with his confrontation with Pershing in 1917, Marshall’s fellow participants assumed his compulsion to express his opinion bluntly, yet honestly, spelled the end of his career in Washington.

To his credit, Roosevelt recognized Marshall’s character and came to value his unfailing honesty. In April 1939, Marshall was summoned to the White House, and Roosevelt selected him to become Chief of Staff of the Army, vaulting him over several dozen more senior officers. Marshall was honored, but he made clear in his response to the President, that, he had the habit “of saying exactly what I think, and that can be unpleasing. Is that all right?” Roosevelt’s acceptance with a grin only inspired Marshall to remind the President again that his candor might be unpleasant. Roosevelt maintained his grin and said with resignation, “I know.” That exchange cemented the terms of probably the most important operational relationship in American military history.

The Marshall Plan

As Secretary of State, Marshall had an enlightened and visionary attitude toward dealing with Europe after World War II. The world wanted to punish and punish harshly –particularly Germany. Yet Marshall believed that to support and stabilize Europe, a conciliatory approach to reconstruction, including that of Germany, was absolutely necessary.

Devastated European countries were being tempted by communism because it represented hope from post-war economic, political, and social despair. To ensure freedom, Marshall and others imagined a program that would restore the economic health of Europe – a program that would rely on countries acting cooperatively with the aid and assistance of the United States.

What is now known as the Marshall Plan was broad-based, and dealt with critical issues such as trade agreements, loan repayments, and financial aid. It was not unanimously embraced. Many Americans, including some members of Congress, favored isolationism. The Soviets did not want to reveal their needs to other countries or accept East-West trade, which would ruin their plan to control the commerce of the Eastern Bloc. France, which had been invaded three times in a century, did not want a strong Germany. Again and again, however, Marshall stressed that a strong Germany was a strong Europe. By December 1947, Congress had approved a $600 million measure to provide temporary aid to Western Europe. A few days later President Truman sent the European Recovery Program (the Marshall Plan) to Congress for its approval.

By the time the plan had been administered in 1951, more than $13 billion had been distributed to the 17 participating countries. (That’s about $140 billion in 2020 dollars.) Europe’s Gross National Product rose 33 percent, industrial production increased 40 percent, and by 1953, trade between European countries increased almost 40 percent.

The Marshall Plan laid the groundwork for the modern European Union, and it is considered by many to be the most successful foreign aid program of the 20th century.

The Marshall Nations

Austria

Belgium

Denmark

France

Germany

Greece

Iceland

Ireland

Italy

Luxembourg

Netherlands

Norway

Portugal

Sweden

Switzerland

Turkey

United Kingdom

Interested in Knowing More About Marshall?

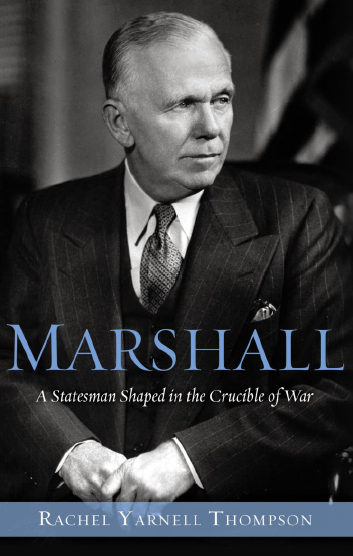

Rachel Yarnell Thompson's Marshall: A Statesman Shaped in the Crucible of War begins with a sandy-haired, mischievous, and energetic boy, nurtured by his mother, judged and challenged by his father, and deeply loved by both.

Thompson has taken Marshall from that fresh-faced youth's tentative and formative time to the intersection of national and world events where he soon proved his mettle as a leader. Combining extensive primary source material with secondary sources, Thompson's biography presents an authoritative and superbly readable story of George C. Marshall's extraordinary journey.