A Time for Leadership: Japan’s Surrender and the Dawn of a New Nation

Eighty years ago, the final chapter of World War II in the Pacific ended not only with devastation but with a timeless lesson in visionary leadership. Announced on August 15 and signed formally on September 2, 1945, Japan’s unconditional surrender set in motion a remarkable transformation—from militarist empire to peaceful democracy, from devastation to prosperity.

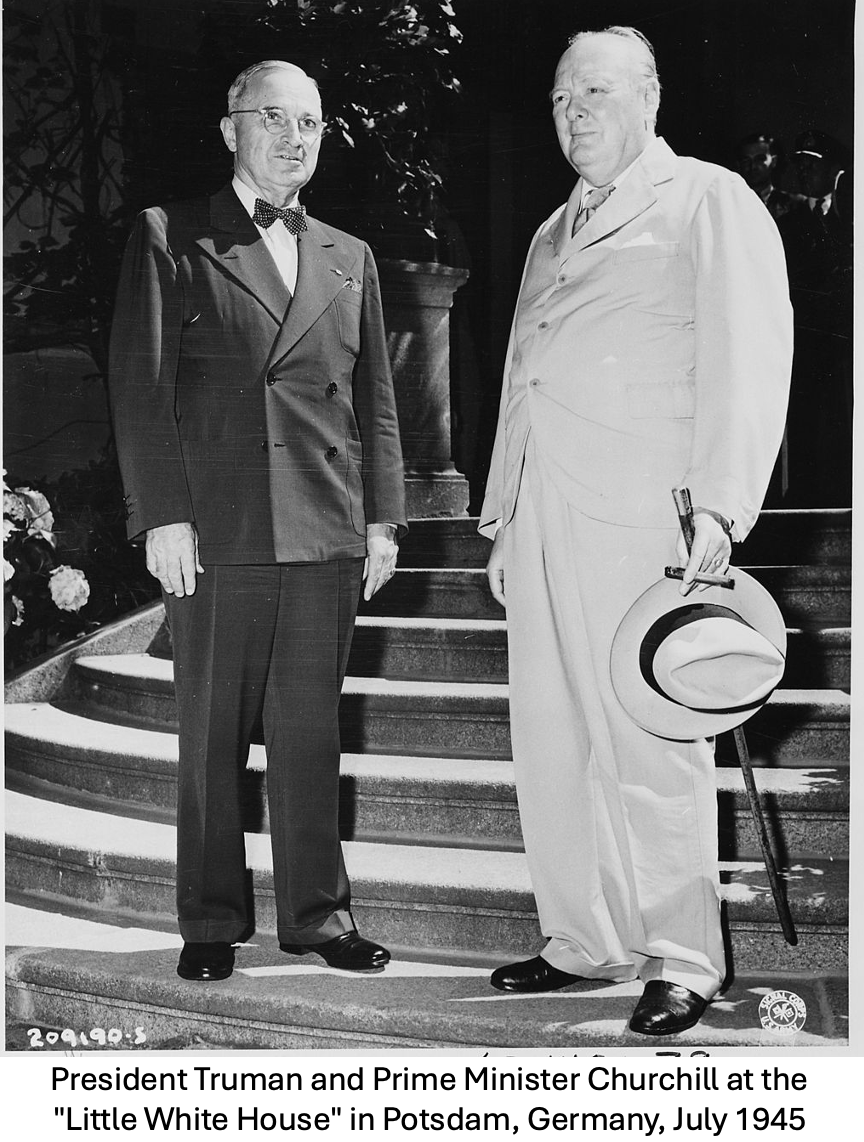

For Emperor Hirohito and Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki, it was a moment of reckoning in defeat. For U.S. President Harry Truman and his senior military leaders, it was a test of responsibility in victory. The period offers enduring lessons in vision, restraint and the will required to lead in crisis.

Unconditional Surrender and a Reluctant Enemy

On July 26, 1945, the Potsdam Declaration demanded Japan’s unconditional surrender, warning of “prompt and utter destruction” if the nation continued to resist. Critically, the declaration made no mention of the future of Japan’s Emperor (the spiritual symbol of the nation) —a telling and deliberate omission addressing a society in which the imperial institution was sacrosanct.

By late July, Japan’s military situation was hopeless. Its cities lay in ruins; its navy was decimated; and the invasion of the home islands loomed. Yet within Japan’s wartime cabinet, a powerful faction still resisted surrender, hoping for better terms—or even a last-second Soviet mediation.

Then came the atomic bombings of Hiroshima (August 6) and Nagasaki (August 9)—unprecedented in scale and devastation. On August 8, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria, wiping out any remaining diplomatic options.

Despite catastrophic losses and impossible odds, Japan’s leaders remained divided. For many in the military, surrender meant national humiliation. Soldiers were trained to die rather than yield, and civilians were indoctrinated to fight to the last breath. The military leaders extended these principles to include the entire nation if necessary.

Against this stark backdrop, Emperor Hirohito took the extraordinary step of intervening directly, overriding his military advisors and urging surrender. It was an act of moral courage that spared the people of Japan from needless suffering.

The U.S. Dilemma: Surrender Without Humiliation

The U.S. faced a critical leadership decision of its own: does unconditional surrender automatically mean the removal of the Emperor?

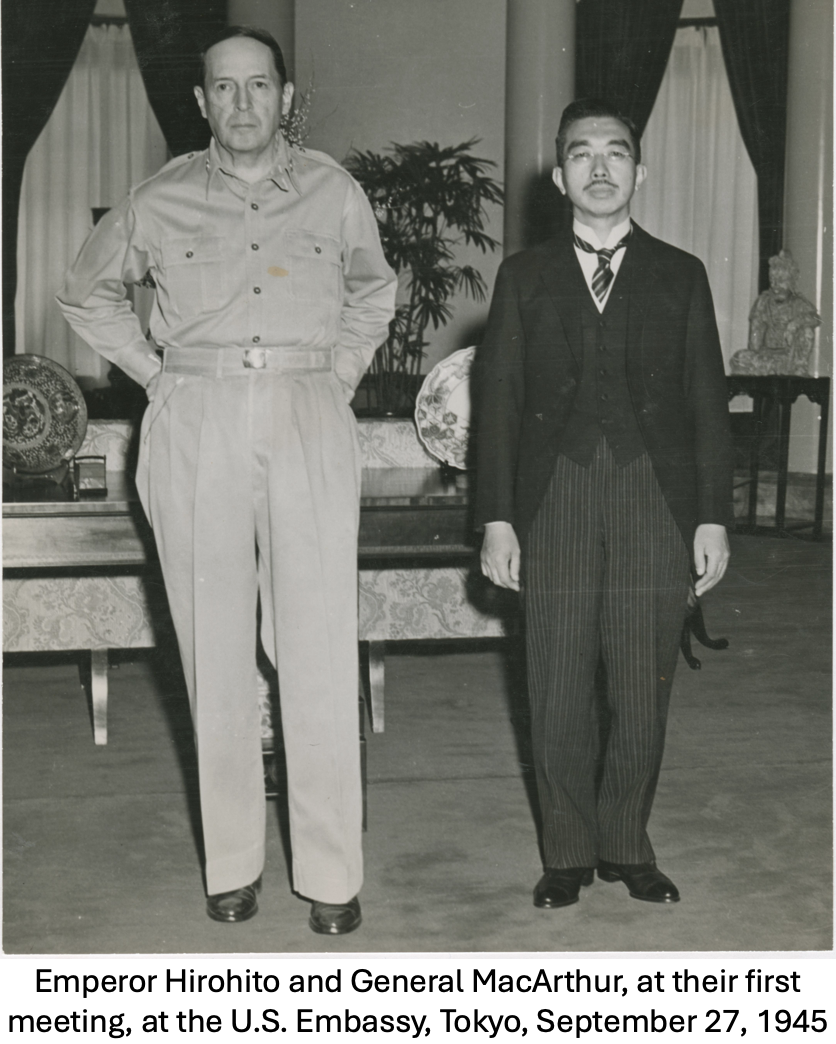

Privately, Truman’s advisors, including Secretary of War Henry Stimson, Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall and General Douglas MacArthur, recognized the Emperor’s symbolic importance. They feared his removal could lead to chaos or unending guerilla resistance. A compromise emerged: Japan would surrender unconditionally, but the Emperor could remain—as a constitutional monarch stripped of political power.

This calculated decision was never formally promised before surrender but was quietly signaled through diplomatic channels. Marshall and his staff assessed that hardline elements of the Japanese armed forces would be more likely to surrender under the Emperor’s command. It helped bring the war to an end without further bloodshed—and without the utter humiliation that might break Japan’s national spirit.

The Occupation Begins: MacArthur’s Moment

With surrender announced on August 15 and signed aboard the USS Missouri on September 2, the U.S.-led occupation began under General MacArthur, who served as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP).

He wielded near-total authority. His leadership style—part authoritarian, part visionary—earned him a curious nickname in Japan: the “American Emperor.” But, despite his outsized ego, MacArthur chose a wise path of restraint and reform.

He governed not through vengeance but through transformation: releasing political prisoners, legalizing labor unions, expanding women’s rights and revamping education. Above all, he oversaw the drafting of a new constitution.

A Constitution Written in English, Embraced in Japanese

On January 1, 1946, Hirohito issued the Ningen-sengen (“Humanity Declaration”) renouncing his divine status. This moment marked the symbolic and very real shift from the age of imperial absolutism to democratic accountability.

In early 1946, a team of U.S. officers drafted a new Japanese constitution in just over a week. While technically imposed by the occupiers, it was accepted and even embraced by Japanese leaders eager to rebuild.

Promulgated in May 1947, the constitution enshrined sovereignty of the people, civil liberties and women’s suffrage. Most famously, Article 9 renounced war, committing Japan to constitutional pacifism—an unprecedented move for an independent nation, much less a former empire.

Rebuilding the Free World: The Marshall Plan and the Japanese Model

The rebuilding of Japan occurred alongside America’s broader postwar vision: not just to win peace, but to build a freer, more stable world order. In Europe, this vision took form in the Marshall Plan – a massive humanitarian and strategic investment in democratic stability.

In Japan, similar principles guided U.S. policy. The U.S. provided billions in aid, encouraged democratic reforms and shielded Japan under its military umbrella, allowing it to prioritize economic growth over rearmament.

Thanks to wise leadership at all levels, the U.S. acted with strategic foresight, not revenge. By retaining the Emperor and investing in reconstruction, it closed the door on Soviet influence in Japan and turned a former enemy into a Cold War ally and key economic partner.

The occupation would officially end in 1952, but the U.S.–Japan alliance has endured as a cornerstone of Pacific security, even as adversaries have shifted. In the decades after the war, Japan emerged as a stable democracy and one of the world’s leading economies.

American decision-making at the end of the war—marked by devastating force, calculated diplomacy and forward-looking governance—shaped not only the outcome of World War II, but the postwar order in Asia. The result was a model for post-conflict transformation and an enduring example of what restrained, visionary leadership can achieve. Eighty years later, the end of a global conflict serves as a powerful reminder that true leadership is not about winning wars—it is about shaping peace.